How Many Animals Have Bones In Their Penis

For ferrets, sex activity is a prolonged affair. In total, the act of mating might last upward to iii hours. Fortunately for the males of the species, they are packing a secret weapon to assistance them through this daunting task. Some modernistic mammals (including ferrets, mice, dogs and even apes) have a bone inside their penis, called the baculum.

The bones have evolved unlike shapes and sizes, from the water ice-cream scoop form of the dear badger to the long thin osseous bone of a blackness acquit. Information technology has always been a bit of mystery as to why some species of male mammals evolved basic in their penises. Humans are actually unusual in this respect, equally our species has lost the mineralised os in place of a small ligament in the tip of the penis.

In animals possessing a baculum, males with wider penis bones have been shown to male parent a larger number of offspring. Yet exactly how the penis bone impacts on male fertility has remained a puzzle.

Protecting the urethra

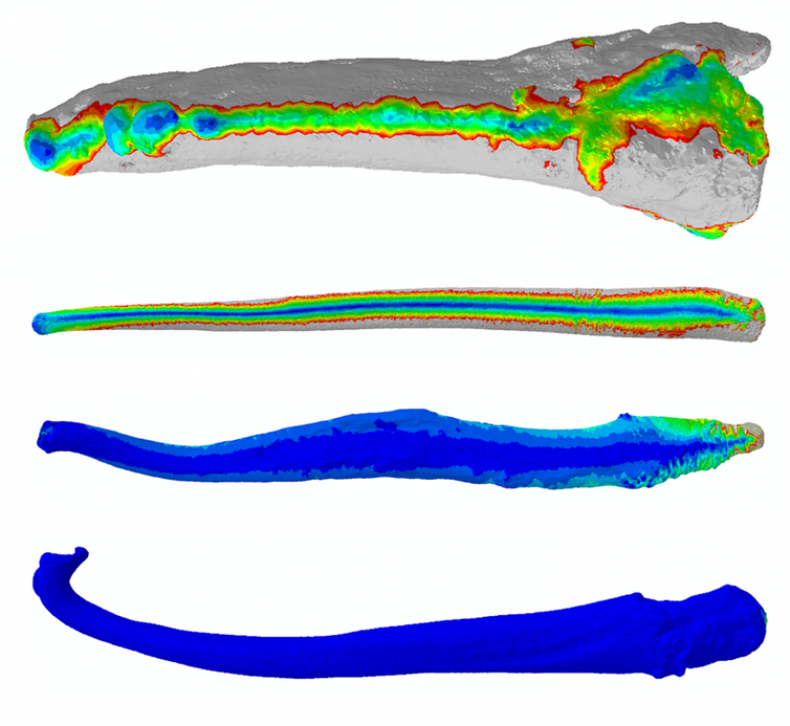

However, our new research—which used innovative 3D scanning and technology-inspired computer simulations – has revealed that in carnivores (the group including cats, bears, dogs and weasels), the baculum may help males breed for extended periods of time. The "prolonged intromission" hypothesis suggests that the penis bone has evolved to protect the urethra (the tube responsible for delivering sperm) when sex becomes a lengthy endeavor.

Other studies accept found mixed evidence in support of this idea, some in favour and some against. In role, this might be due to important features of the baculum previously being ignored. Penis bones are notable for being extremely diverse in shape, with species being distinguished by possessing bizarre tips, ridges and grooves. Nonetheless in the past, biologists take only included the about basic metrics (bone length and diameter) into their models of baculum function.

Virtually 'crash-testing' the penis bone

To accost this oversight, nosotros used a digital modelling technique more familiar to engineers and physicists. In "finite element analysis" (FEA), a 3D reckoner model is most "crash-tested" in social club to calculate how potent the object is. The method is more than commonly applied to structures such as bridges or race cars, as a way of predicting their performance without physically damaging the object.

The major benefit of FEA is that the whole 3D shape of the baculum tin exist incorporated into our estimates of os strength. Our results propose that animals breeding for very long durations typically have penis basic that are much stronger than their fast-mating relatives.

Where are all the females?

Previous research, including our ain study, has tended to focus heavily on male anatomy, to the exclusion of females. In mammals, less than a quarter of all studies investigating the evolution of genitals have included both sexes. This bias may partly stalk from practical issues—male genitals are oftentimes made up of rigid difficult parts sitting outside the body, making them easier for scientists to study. But it may also reverberate a historic misconception of the female reproductive organization as being a "passive" vessel, compared to more "active" male structures.

This means we take potentially overlooked of import interactions betwixt the sexes. Thankfully, with the awarding of new X-ray imaging techniques and calculator modelling, our awareness of female genital anatomy is beginning to catch up. We are now extending our study to also include the size and shape of the vaginal tract and to capture the alive motion of the genitals during mating, equally a more than holistic approach to studying animal reproduction.

Charlotte Brassey, Enquiry Boyfriend in Animal Biology, Manchester Metropolitan Academy and James Gardiner, Research Associate in Musculoskeletal Biology, University of Liverpool

This article is republished from The Chat under a Creative Commons license. Read the original commodity.

Source: https://www.newsweek.com/why-do-some-mammals-have-penis-bone-evolutionary-puzzle-explained-1132322

Posted by: fleishmanthorm1942.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Many Animals Have Bones In Their Penis"

Post a Comment